In 2020, L.A. taggers are rarely killing anyone in a fight over a painted-over piece.

In contrast, taggers are often drawn to street art or graffiti-based murals, leaving their signatures on the coattails of well-photographed pieces. While the traditional L.A. graffiti beef between crews and taggers of painting over each other’s work resounds to this day, the newbies’ fame-grabbing move can be the seen spot. Some well-known L.A. artists have come to expect that their murals have bullseyes on them.

Among graffiti’s many unwritten rules is to not paint over someone else’s work, and then only if your piece or production is going larger in size. One drive through L.A. shows that rule is constantly broken, with scores of marked-up street art and graffiti murals. Graffiti’s street rules, though, are more intricate and subtle than that generalization, and a nuanced understanding is gained with time invested in the community.

A mural in Hollywood tagged by Bat and Ola (Photo by Nicholas White)

“This is always a famous line: ‘Wow, I love all this beautiful work, but I fucking hate the tagging. Why do they have to do that?’” Vyal, an L.A. native and local graffiti artist since the late 1980s, says of tolerating taggers, when hitting his or others’ more detailed street works.

“Well, you don’t understand,” Vyal says. “Tagging is, more than likely, late teens and early teens, so this is their introduction to the work. Kids that age may not have access to a wall or a lot of paint, but they know they’re interested in this type of work and want to eventually get to that point, as most graffiti artists and writers do.”

Vyal’s multi-dimensional, portal-like eye murals oversee the city, from Venice to East L.A., harkening to the graffiti goal of being all-city. His work, too, is occasionally tagged. He has a large wall off Alameda in the Arts District, a collaboration with longtime local graffiti titan Risk. This collab-pedigreed wall, too, is vulnerable to taggers, Vyal says, adding that he often does low-level clean-ups and paint-overs on the prestigiously placed wall.

Taggers can take an entirely different point of view on wall installations and graffiti art, to the chagrin of some and delight of others. The walls belong to the public, graffiti tagger Bat says, and are up for grabs when it comes to ownership, even if they are covered with another painter’s work.

“The walls belong to us. Regardless of what it has on it, it’s gonna get hit,” Bat says. “And, if it’s a mural that gets gone over, the artist will probably be paid to go fix it. So, as far as I’m concerned, we’re creating jobs. They can complain, but it’s essentially job security for both sides.”

This, of course, is mostly not the case, as not every artist has Shepherd Fairey’s big-business support. Some mom-and-pop grocery stores with modestly painted spreads of fruits and vegetables can also suffer the blight of taggers and be left with the chore of fixing vandalism. In the speed of life and with limited resources, this can often go unaccomplished.

Bat, who spends time in L.A. and New York City, has hit numerous art spots around town with a simplistic black symbol, occasionally with a streak of red. He takes pride in leaving his mark on other works.

“I’m just out here painting bats on other people’s shit,” Bat says. “There’s always backlash. And I couldn’t care less. We were here first. The people who do the murals don’t own the property. In the end, it’s just layers of paint on a wall.”

A tagged phone-booth electrical box by Gaso in the Arts District (Photo by Nicholas White)

Another of graffiti’s rules is that the more remote and socially isolated the artist, or the less locally connected, the more likely their work is to be hit by taggers. Community roots help keep pieces protected, as shown in some of the sparklingly clean Kobe Bryant and Nipsey Hussle murals for the L.A. icons. In the Black Lives Matter summer 2020 protests, Bryant murals were sometimes the only spared, unvandalized properties on the block.

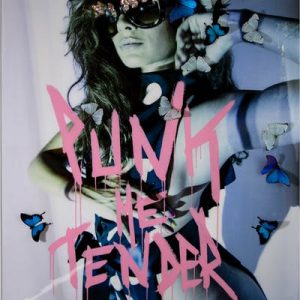

“This is where experience comes in. There are invisible rules in the street,” says graffiti-inspired street artist Punk Me Tender, a Parisian-born, 17-year resident of L.A. unconnected to L.A. graffiti crews. Like many, he has had pieces hit several times by the same taggers. “It comes in many layers. It comes in the form of respect, understanding the scene – it’s seeing who did what and why did they do it.”

The floodgates open to taggers when tags multiply on a wall installation without the maintenance to keep it clean and unaffected.

“In general, as soon as I see tagging or things like this, I fix it right away,” Punk explains. “This is just for me to show that I’m active, and that I keep my shit alive. Because if you don’t do it, they think you’re out of the game. You lose your respect, your street cred.”

Punk Me Tender’s pink and black accented pop-punk style pieces around the city are well known, highlighted by a 3D mural wall of birds flying on the back of the old Amoeba Music in Hollywood. This piece replaced in 2019 a large butterfly mural that had become ravaged by taggers.

Punk Me Tender in Hollywood

“There are guys like Retna, for example, who I respect a lot,” Punk says. “He has a massive street cred. He has a big crew behind him. Nobody fucks with him because they’ve been in town for years and years, and that’s normal. I don’t have a crew.”

To some old-timer graffiti artists, vandalism over pieces used to mean something of more substance. The Art of Chase, whose trademark Salvador Dali-inspired eyes dot buildings around L.A., started many decades ago as a tagger. The veteran artist has noticed a shift in why taggers are drawn to a certain type of painting to cover.

“I’m from the school where if you tag on someone’s piece, that’s beef,” Chase explains. “Kids worldwide now do it. But they don’t do it for beef reasons. They know then their tag is going to get noticed. This big wall is getting so much attention. When you see a tag on some big wall, that tag is going to get some fame, so they think.”

In response to what can be an inevitable fate for their pieces, resourceful street artists combat the frustration and boredom of fixes by treating each trip to the neighborhood as a networking experience. Talking with shopkeepers and exchanging business cards, Chase, when making his fixes, would prefer to not know who tagged his piece. Out of sight, out of mind — he just wants the tag removed.

“I’m just turning the fan on and moving it out of there,” Chase says. “I don’t want beef with anyone. I don’t want to get upset. I don’t want to know the name.”