The emerging data on mental health during the pandemic suggests a troubling future. Surveys show that Americans have become more depressed and anxious, and experts in a variety of fields have argued that Covid-19 has changed society forever.

While the pandemic has undeniably caused extraordinary stress and sadness, research on human resilience suggests that people will recover from the trauma of the pandemic faster than many believe. And while certain groups may need mental health care for the longer term, it’s also true that humans’ ability to overcome adversity is often underestimated and that an overwhelming majority of people who suffer trauma will not develop mental illness but eventually feel better.

As a psychiatrist, I see this firsthand with patients and colleagues. Most of my patients who had clinical depression and anxiety before the pandemic did not deteriorate during the pandemic. Yes, they were stressed and worried, but I was struck by how this group remained pretty stable.

Earlier in the pandemic I also ran a support group for the anesthesiologists at the hospital where I work. Every day this group of men and women would intubate people with severe Covid-19, exposing themselves to the virus and immense patient suffering. But eventually, the support group disbanded because the members felt they could cope without my help.

This is not to suggest that the impact of Covid-19 on mental health isn’t real, nor that it won’t be long-lasting in some cases. It is real, and it will linger for many. But it’s also important to underscore that most people who are exposed to stress and trauma do not necessarily develop clinical depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. Sure, they experience anxiety and sadness, but these mental health states can lift soon after stress abates.

Studies suggest that up to about 90 percent of Americans have experienced a traumatic event, yet the prevalence of PTSD is estimated to be 6.8 percent. So while exposure to traumatic events is common, only a small minority of people develop PTSD as a result. Follow-up studies of trauma victims with PTSD in the general population show that the symptoms decrease significantly within three months after trauma and that about 66 percent of those with PTSD eventually recover.

Trauma does not reliably produce illness, which is important to remember when looking at how people are responding to the pandemic as it unfolds. A recent study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that from August 2020 to February 2021, the percentage of adults with recent symptoms of anxiety and depression increased to 41.5 percent from 36.4 percent.

But most surveys like this assess symptoms at a given point in time, which could turn out to be transient. These surveys are also conducted online, using rating scales that don’t reliably establish a clinical diagnosis. Other research tracking people with diagnosed mental health conditions haven’t found an increase in symptom severity during the pandemic.

I’ve found that many patients find comfort in learning that most people who are traumatized do not develop psychopathology. The ability to cope with adversity is the essence of resilience — but it doesn’t mean there is no psychological distress. To the contrary, anxiety and sadness are common reactions, but these responses are typically manageable and temporary.

It’s why many people who experience intense stress or trauma go on to live healthy, productive lives. Not all stress is harmful to the brain, and many people cooped up at home during the pandemic largely faced a kind of manageable stress. Once normal life can resume, many people will begin to feel much better.

Chronic unremitting stress that isn’t easily resolved, however, leads to sustained increase of adrenaline and cortisol and can be harmful. Frontline workers were exposed to this type of chronic stress during the pandemic and thus are at much higher risk of developing clinical depression and anxiety. The pandemic also took a disproportionate toll on people of color, who experienced increases in suicide rates in 2020 while overall suicide rates in the country dropped. Making sure these groups have access to care will be critical for their mental and physical health.

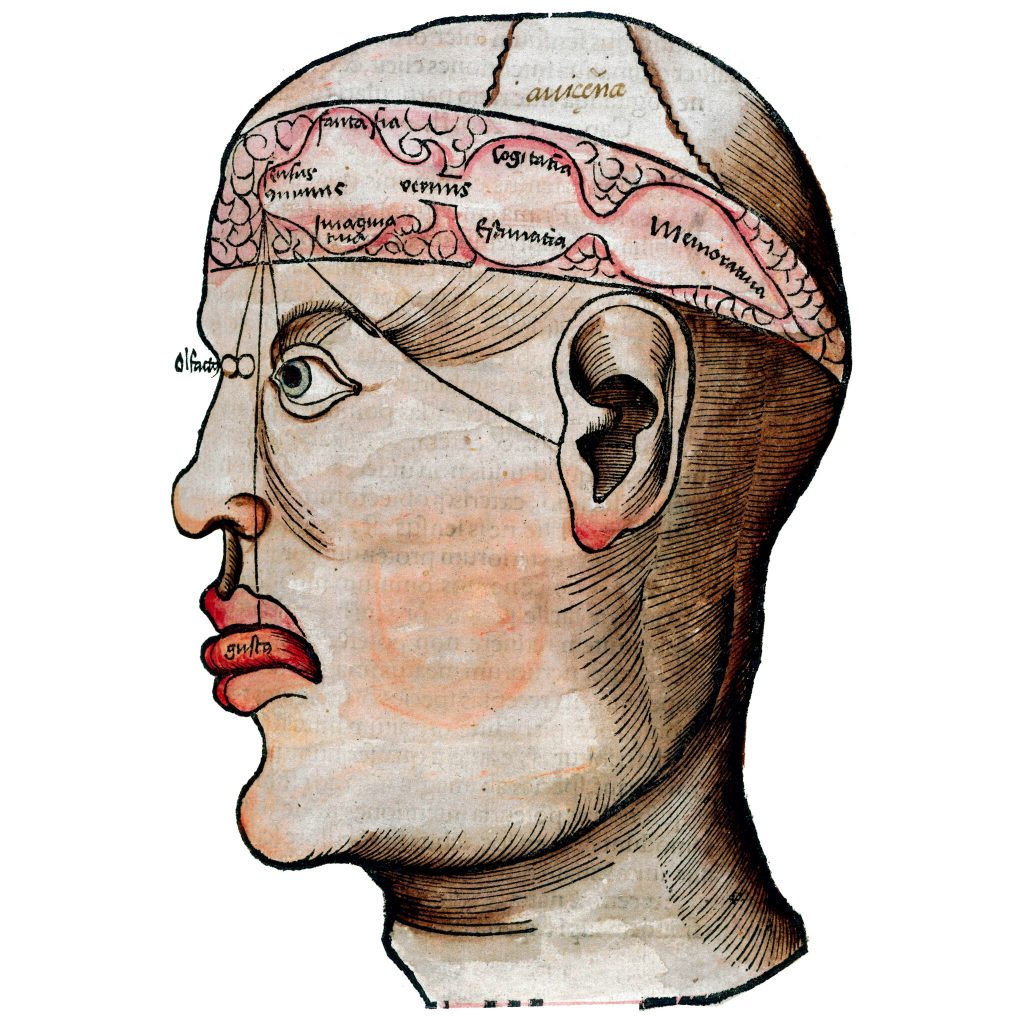

Experts have long been interested in why some people are more resilient than others in the face of stress, including after events like wars and natural disasters. Some of it is genetic, and some of it is a person’s life circumstances. Things like having a steady income, family support and access to health care can affect how people handle traumatic events.

But there are things that people can do to foster emotional and physical resilience, including maintaining social bonds, getting regular exercise and finding ways to reduce stress, among other things. Social support, for example, has been shown to strengthen resilience by increasing self-esteem and the sense of control. Social connectedness also inhibits activation of fear and anxiety circuits in the brain.

There is no question that this has been a stressful and brutal year marked by untold loss and grief. I lost my splendid 94-year-old mother to Covid-19, and I’m still sad. But people should feel a measure of relief at having navigated Covid to this point, and not forget the fact that humans are more resilient than we realize. We can bounce back.

本文作者为 Dr. Friedman is a psychiatrist and an expert in the neurobiology and treatment of mood and anxiety disorders and has done research in depression.

原文出自于 The New York Times 专栏