Do monsters in our imaginations and in the real world generate depictions of monsters in art, ultimately producing work of exceptional creativity? Robert Williams would answer this question affirmatively. As he told an interviewer, “Monsters are the fantasy anthropomorphic creatures that you make up in your head, that you’re attracted to … I love monsters.” And so do his legions of admirers throughout SoCal and beyond.

In his several decades producing darkly narrative paintings — shaped by his early involvement in California car culture working for Ed “Big Daddy” Roth — his contributions to the underground comics scene during the late 1960s and early ‘70s, as well as cinematic settings, graffiti art and psychedelic imagery — the now 78-year-old Williams has played a central role in the Lowbrow art genre. His painting stands out for its meticulous old master style of figurative oil painting, while portraying scenes antithetical to those of high art.

This Lowbrow exhibition, curated by local artists Brennan Roach, Liz Zuniga Roach and Dustin Myers, contains nearly five dozen in-your-face pieces, including prints, an original oil painting, several skateboards and a custom-painted hot rod.

Robert Williams: Patrick Has a Glue Dream, 1989 (Courtesy of the artist)

The thrust of this visual feast is the juxtaposition of conventional scenes with apocalyptic, surreal imagery mined from Williams’ dreams and unconscious self, and even from his exploration of our collective unconscious. The visceral Patrick Has a Glue Dream, for example, illustrates a normal-looking boy building model airplanes while sniffing glue and dreaming of a demonic Hitler head, encased in a yellow bell jar affixed to a red flying octopus that grapples with a bomber flying over the European landscape.

While the pieces in this show span about half a century, from the 1960s nearly to the present, none of the work feels dated, perhaps indicating Williams’ proclivity to see the world as a perennially rebellious child. As he has said, “Every one [of his paintings] is a child that needs discipline.”

Robert Williams: In the Land of Retinal Delights, 1968 (Courtesy of the artist)

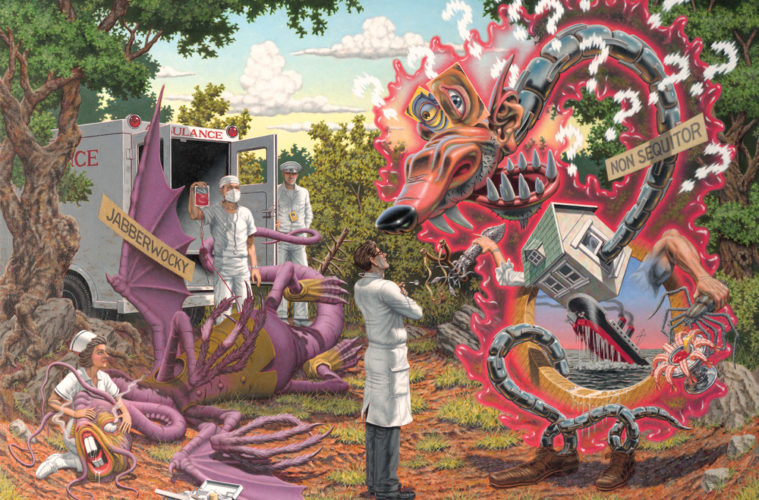

The consistency of this assertion is borne out here in work after work. Death by Exasperation is a parody of a Lewis Carroll poem, featuring a purple Jabberwock in a state of collapse, as an enormous red dragon-like monster looms over the scene. A defiant doctor stands in the midst of this dramatic scene, as a team of EMTs strive to rescue the Jabberwock. The pop surrealist In the Land of Retinal Delights features a large eye dominating a man’s profile. He — or it — stares out at a field of colorful detritus. While stretching the boundaries of realism, the painting cajoles us into opening our own eyes to the world that humankind is creating.

In the Pavilion of the Red Clown, referred to as a tableau vivant (living picture) by Williams, a menacing one-legged clown holding a bird cage containing a snake, torments a beautiful female acrobat. Disassembled masks and prosthetics menacingly inhabit the background. This unseemly look at behind-the-scenes circus performers draws brashly on film noir tropes. The female figures, prominent in this work but scattered throughout his paintings, relate to a long pre-feminist tradition of pulp fantasy illustration, most memorably by Frank Frazetta. The fierce blonde woman in Persuasion of Right Angles is clad in a scant red dress and leopard print tights. She wards off a contingent of robotic men with heads composed of square rods. The symbolism and threatening tone of this artwork is open to interpretation, while its bucolic landscape with trees, houses, streams and skies is askew and disorienting.

Robert Williams: Three Years of Automotive Infamy!, 1983 (Courtesy of the artist)

Williams veers into a darker, doomsday mood in Impervious to Chaos, centering our attention on a family of four praying at their dinner table as demons, devils, fires and explosions, assembled just beyond their home, are about to invade their serenity. This image serves as a testament to Williams’ own chaotic childhood. Equally troubling is the binary composition of Stolen Faces, which has a dozen faceless people in a room alongside what we take to be their smiling severed heads in a foreboding, hellish, shaded foreground in which the monstrous perpetrator lurks.

There is a lighter side to Williams’ oeuvre. As an admirer of old automobiles since his time with Roth, he illustrates vintage cars, albeit with his sardonic perspective. Three Years of Automotive Infamy features four souped up, gleaming 1955-57 Chevys blazing through a ring of fire and defying a muscular devil. With his off-center humor, the artist adds a bikini-clad pin-up to the piece, her back to us as she applies make-up — seated just above his signature.

BigToe: Prickly Heat, 2021 at OCCCA

A group of emerging and mid-career artists, featured in a rear gallery, pay homage to Williams’ example: Jennybird Alcantara, Anthony Ausgang, Adrian Cox, Matt Dangler, Craig Gleason, Naoto Hattori, Parker S. Jackson, Chris Lieb, Laurie Lipton, Amber McCall, Shane Mesquit, Dustin Myers, Peca, Brennan Roach, Johnny Ryan, Isabel Samaras, Scott Scheidly, Greg “CRAOLA” Simkins, Keith Weesner, Casey Weldon, Eric White, Jaime ‘Germs’ Zacarias and Austen Zaleski. His influence on new generations of painters, illustrators and sculptors is an established fact.

Anthony Ausgang: Help is on the Way, 2014 at OCCCA

With its high volume of provocative paintings, along with skateboards and a gleaming, classic hot rod, The Visual Adventures of Robert Williams reflects the bewildering era we live in. While the artist has striven to have his work seen and considered for much of his adult life, he has come to be regarded as the old master that he dreamed about and rebelled against all those years ago. He always had an audience; by now it has caught up with him.

On view at Orange County Center for Contemporary Art (OCCCA), 117 S. Sycamore St., Santa Ana through Jan. 29; occca.org.

Adrian Cox: The Birth of Spirit Gardener, 2020 at OCCCA

This story first appeared at Visual Art Source, an online platform for listings, features and reviews covering Southern California and the Midwest art scenes.

Jennybird Alcantara: The Whisper, 2020 at OCCCA

Greg “CRAOLA” Simkins Is This Your Card?, 2021 at OCCCA