Memories and recollections of live exhibitions can provide solace to art lovers, as we wait for the pandemic to abate and for life to return to a semblance of normalcy.

Among the most outstanding exhibitions I have seen over the years — actually a collaboration of art shows, titled “Pacific Standard Time (PST): Art in LA 1945-1980” — ran from October 2011 to March 2012. For this Getty Foundation sponsored initiative, over 60 Southern California art institutions looked back at, defined and documented in displays, catalogs and dialogues this area’s post war cultural scene.

As these shows demonstrated, influences on the emergence of SoCal as a major art capital included the counterculture movement, the opening of major art schools (including the UC Irvine art department), and the growth of the aerospace industry. The latter provided artists with new techniques and materials, such as malleable plastics and acrylic resin/polymer emulsion paint, employed by California Light and Space artists in their art pieces.

Three Pacific Standard Time exhibitions — presented at UC Irvine, the Orange County Museum of Art and the Laguna Art Museum (LAM) — featured the work of UCI artist teachers and students who inhabited their free-spirited art department from the mid 1960s into the early 1970s.

Laguna Art Museum’s “Best Kept Secret,” the most varied of these exhibitions, was on display from November 2011 to the following January. The show’s title was based on UCI art school dean Jill Beck’s (1995-2003) use of “Best Kept Secret” to describe the newly created art school as a formidable force in the advancement of contemporary art.

As the LAM exhibition revealed, UCI in its early days was a haven of forward-thinking creativity where instructors transcended the limits of formal art styles, while employing tolerance, dialogue, diversity and experimentation in their teaching methods. And students were encouraged to explore new approaches to performance art, body art, video and film, among other genres. Or as art writer/poet Peter Frank explained in the catalog accompanying the show: “Instructors stressed attitude rather than practice, intellectual inquiry instead of manual dexterity, discourse in lieu of production.”

UCI art instructors, including SoCal pioneers Larry Bell, Tony DeLap, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, John Mason and Ed Moses, mentored students and even collaborated on art pieces with them. Additional inspiration to teachers and students was provided by the modernist free-form UCI campus buildings, designed by William Pereira. (The 1968 movie, “Planet of the Apes,” about a crew of astronauts that crash-lands on a far-away planet, was filmed on the futuristic-looking UCI campus.)

Perhaps the most famous student to emerge from the UCI art department was Chris Burden (creator of the “Urban Light” [2008] sculpture at the L.A. County Museum of Art) who did several conceptual performance pieces there. In his “Through the Night Softly” (1973), he crawled nearly naked over glass; in “Five Day Locker Piece” (1971), he locked himself inside a locker for five days.

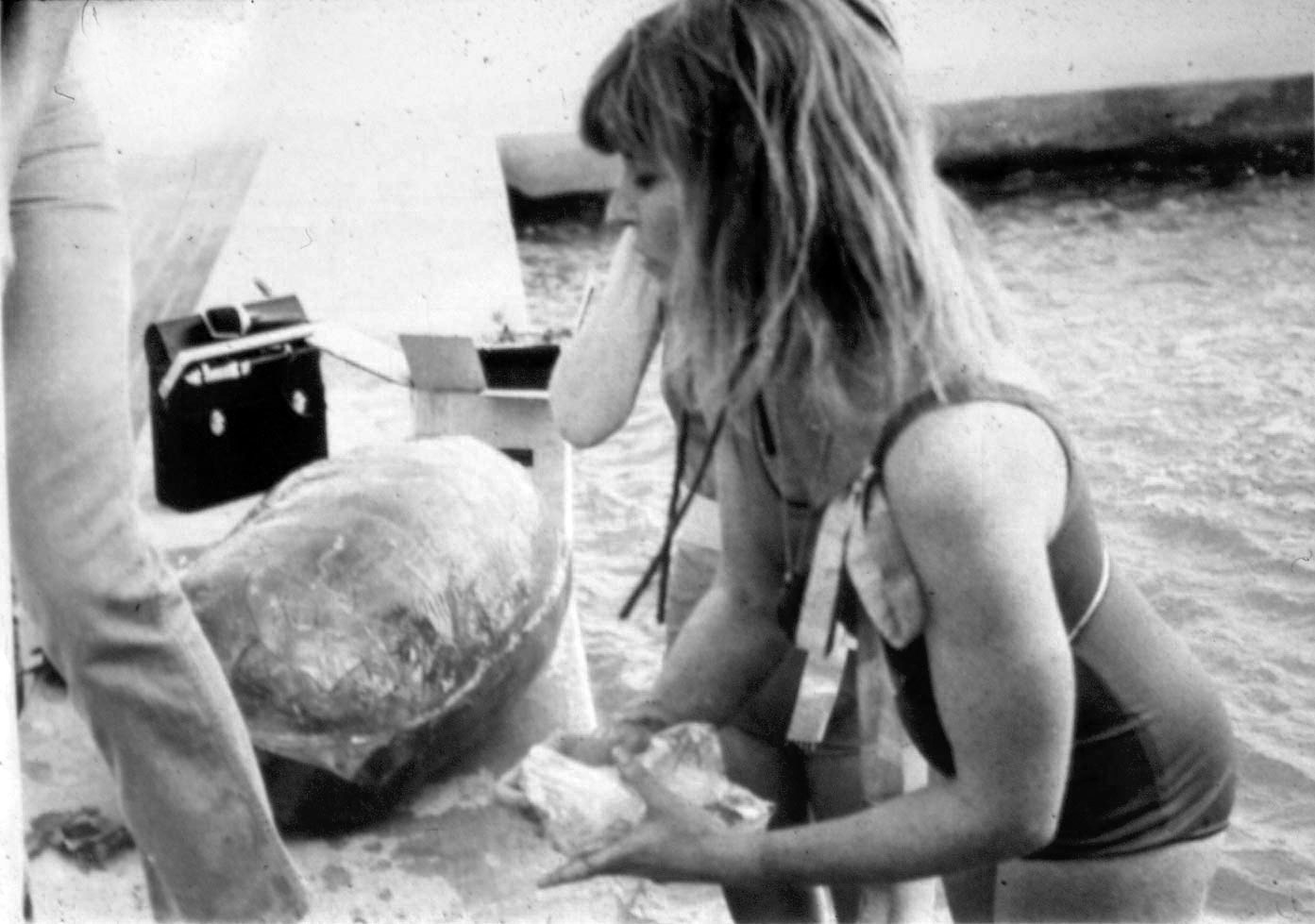

Barbara T. Smith, a former suburban housewife and UCI art student, grew into a performance artist there with her “Ritual Meal” (1969), a nightmarish video of dinner guests wearing hospital scrubs while eating with surgical instruments. Nancy Buchanan created “Hairpiece” (1971-72), a large rug woven from human and poodle hair. And feminist student Marsha Red Adams’ submitted her “Woman Bound/Woman Withdrawn” (1971) to the show. This installation of eight photographs of a naked woman in various constraining poses features hand-painted and stitched string binding each individual pose.

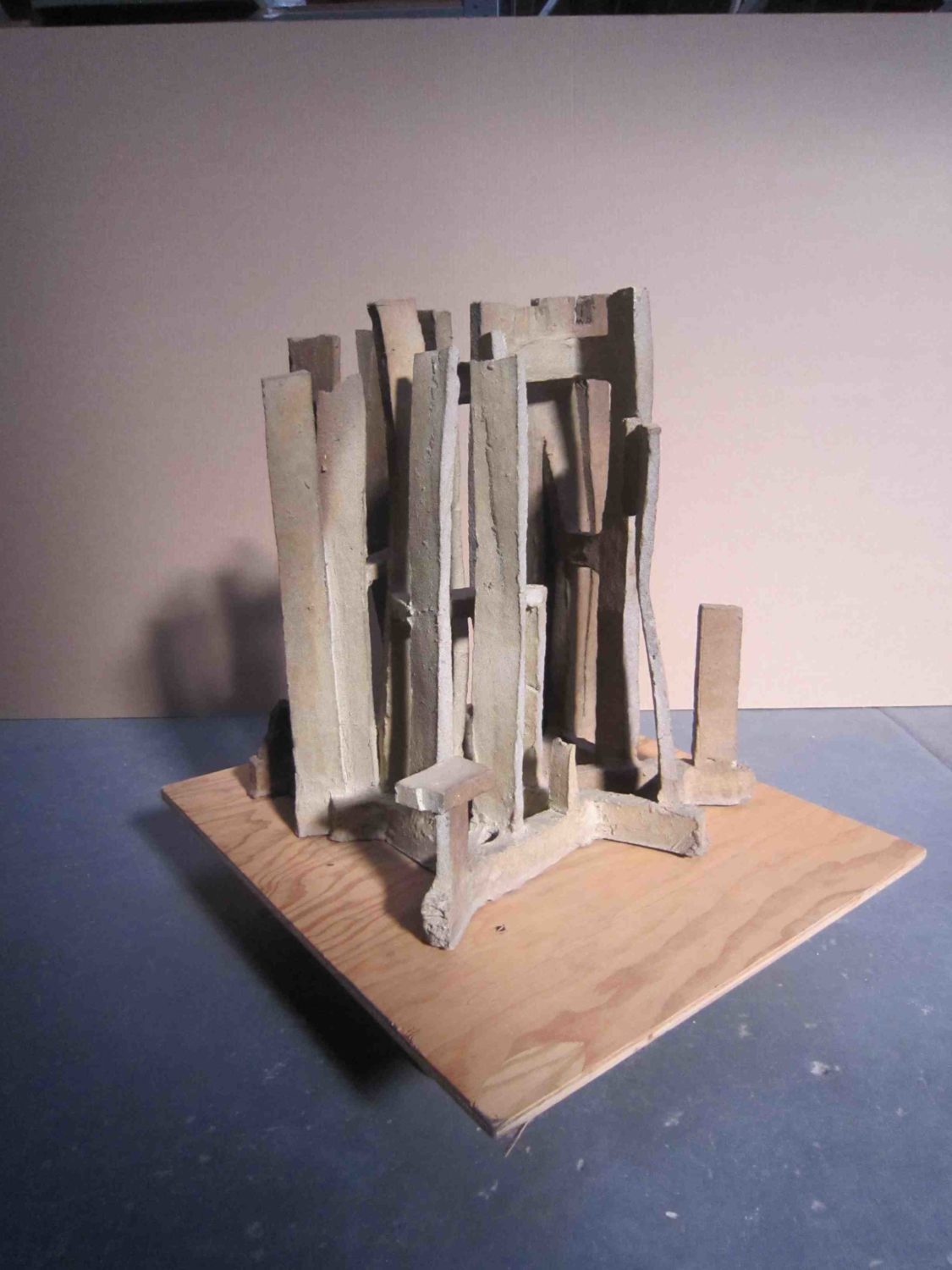

John Mason’s tall “Unfinished Arch” (1973) made of traditional clay bricks was held together through physics and carefully placed components, not with mortar. At a walk-through of the show, he explained how he painstakingly constructed the sculpture, while the museum staff looked on with anticipation.

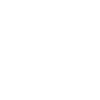

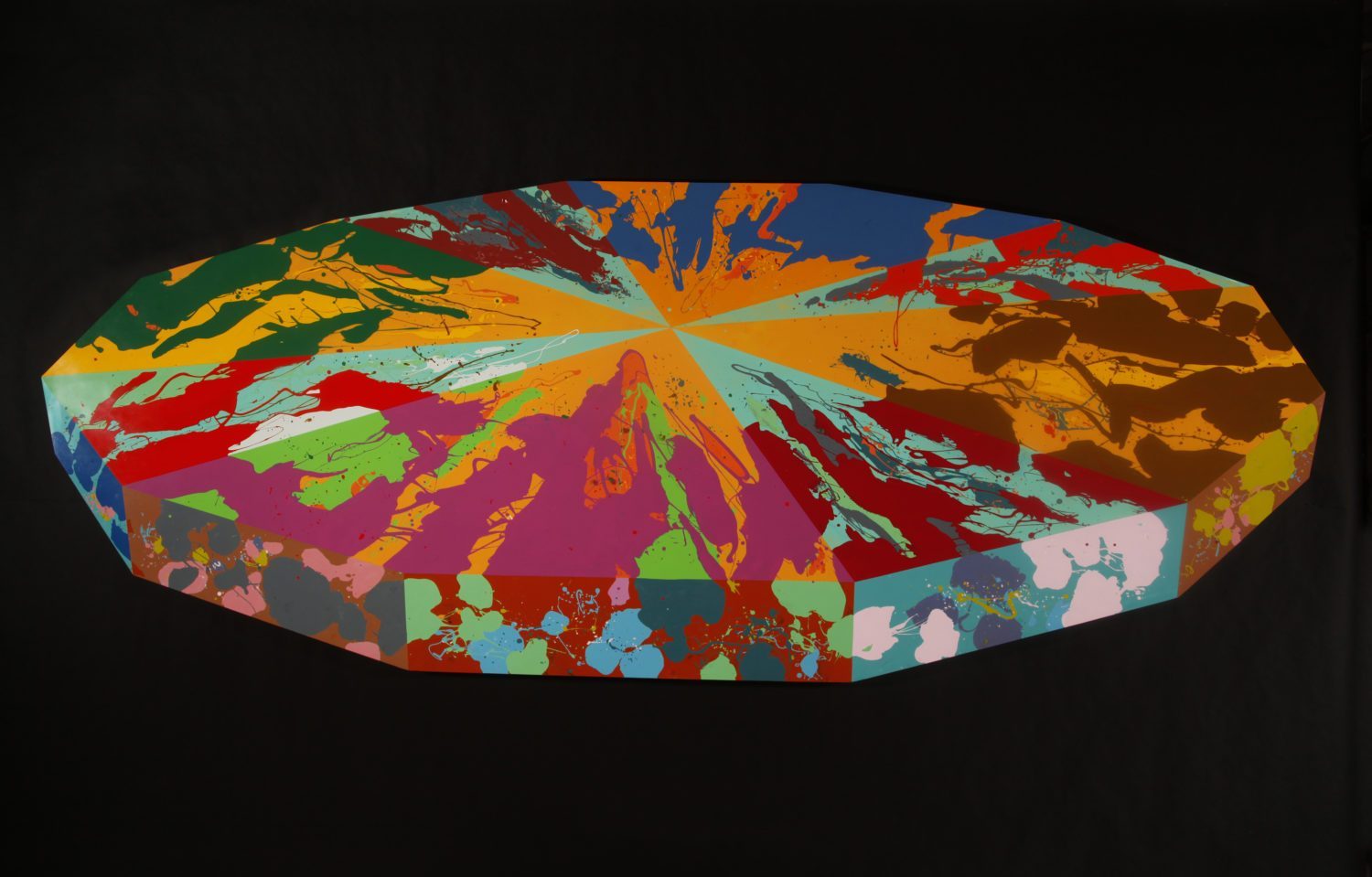

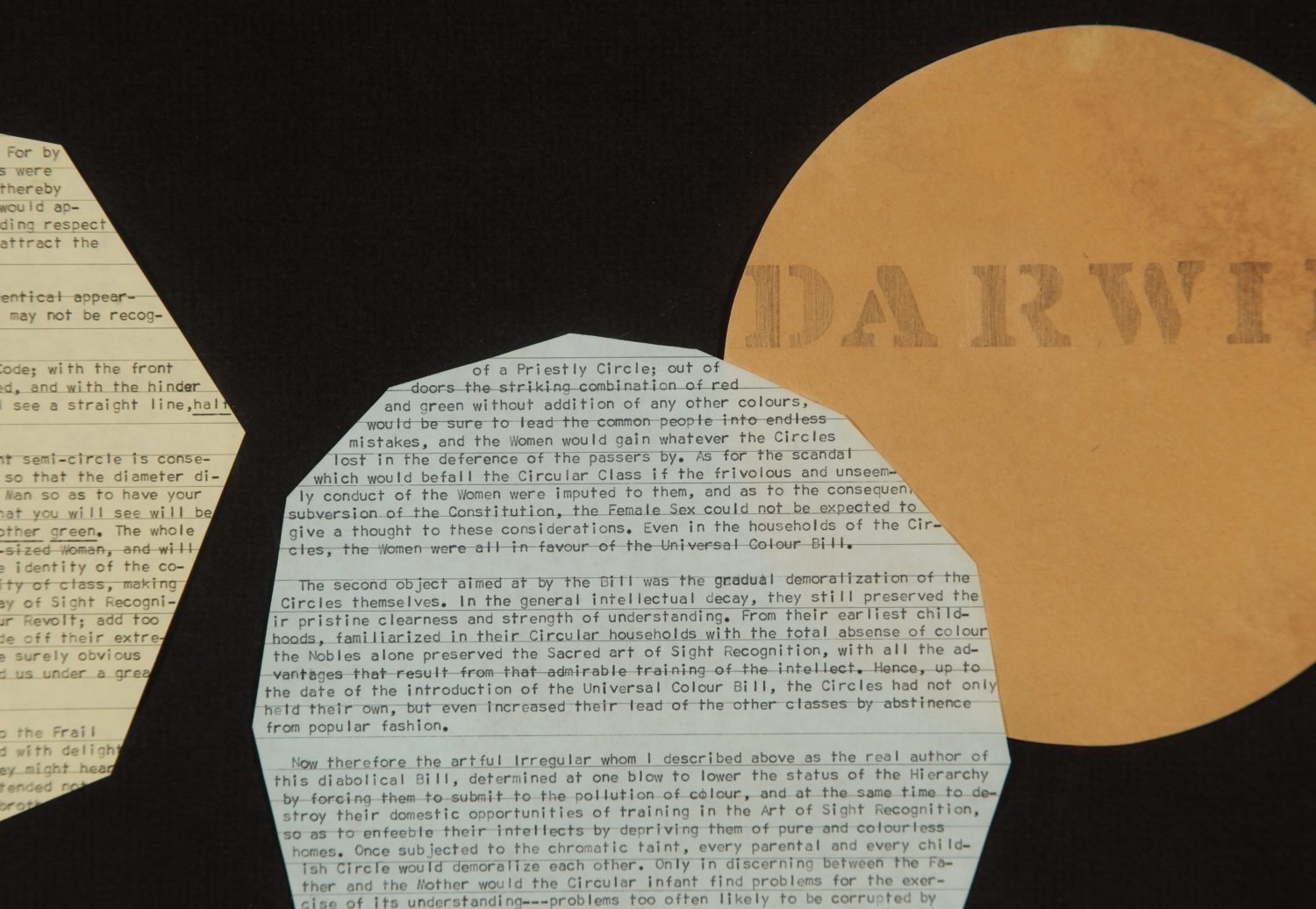

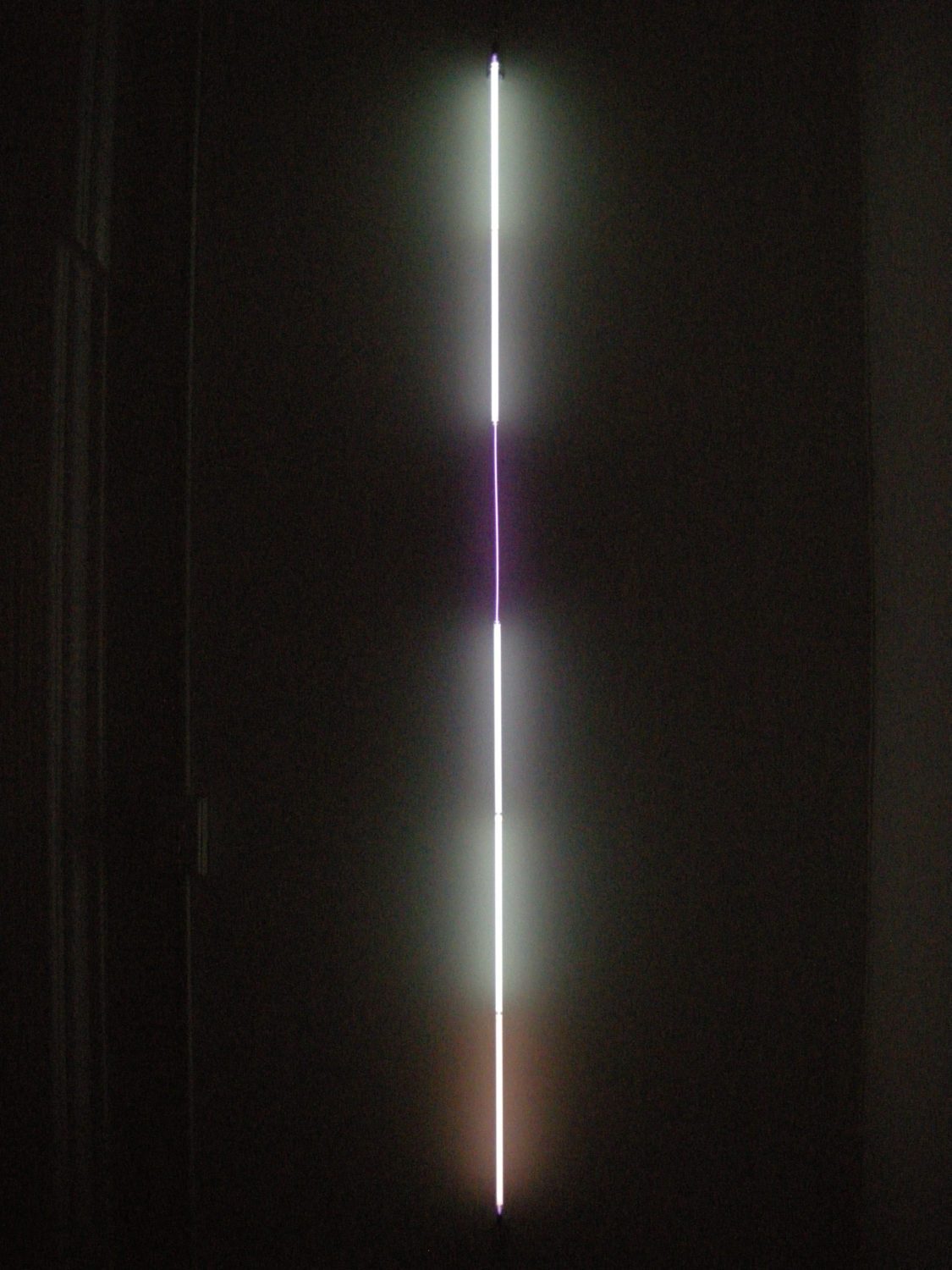

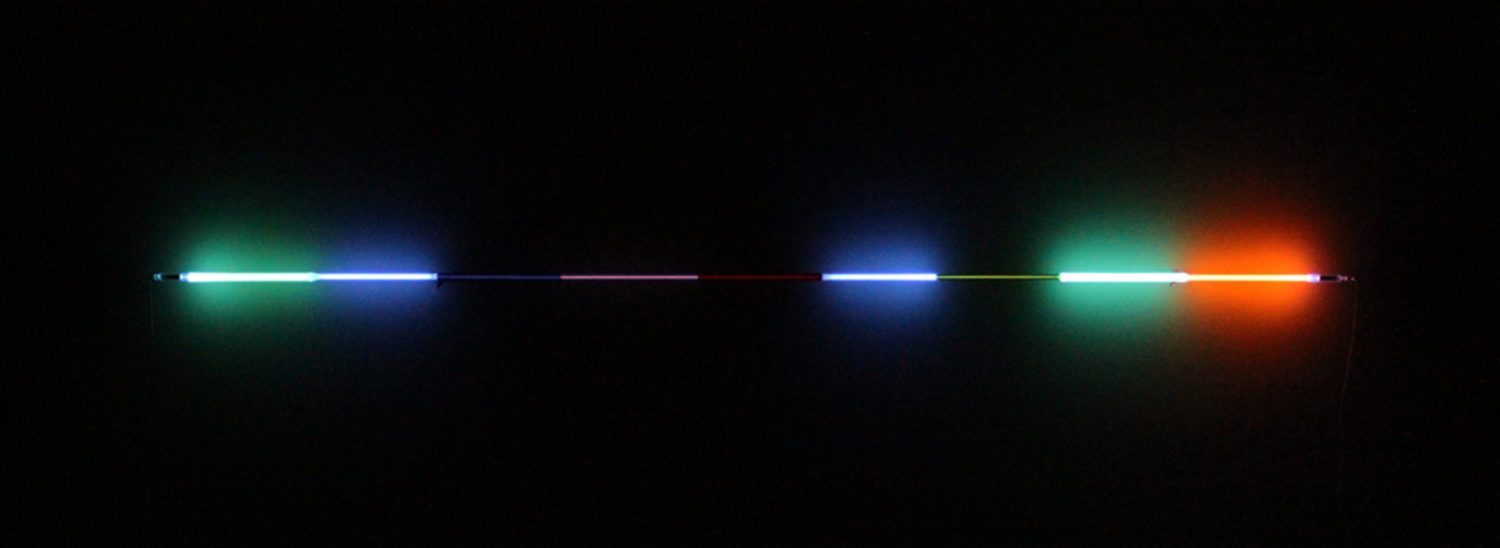

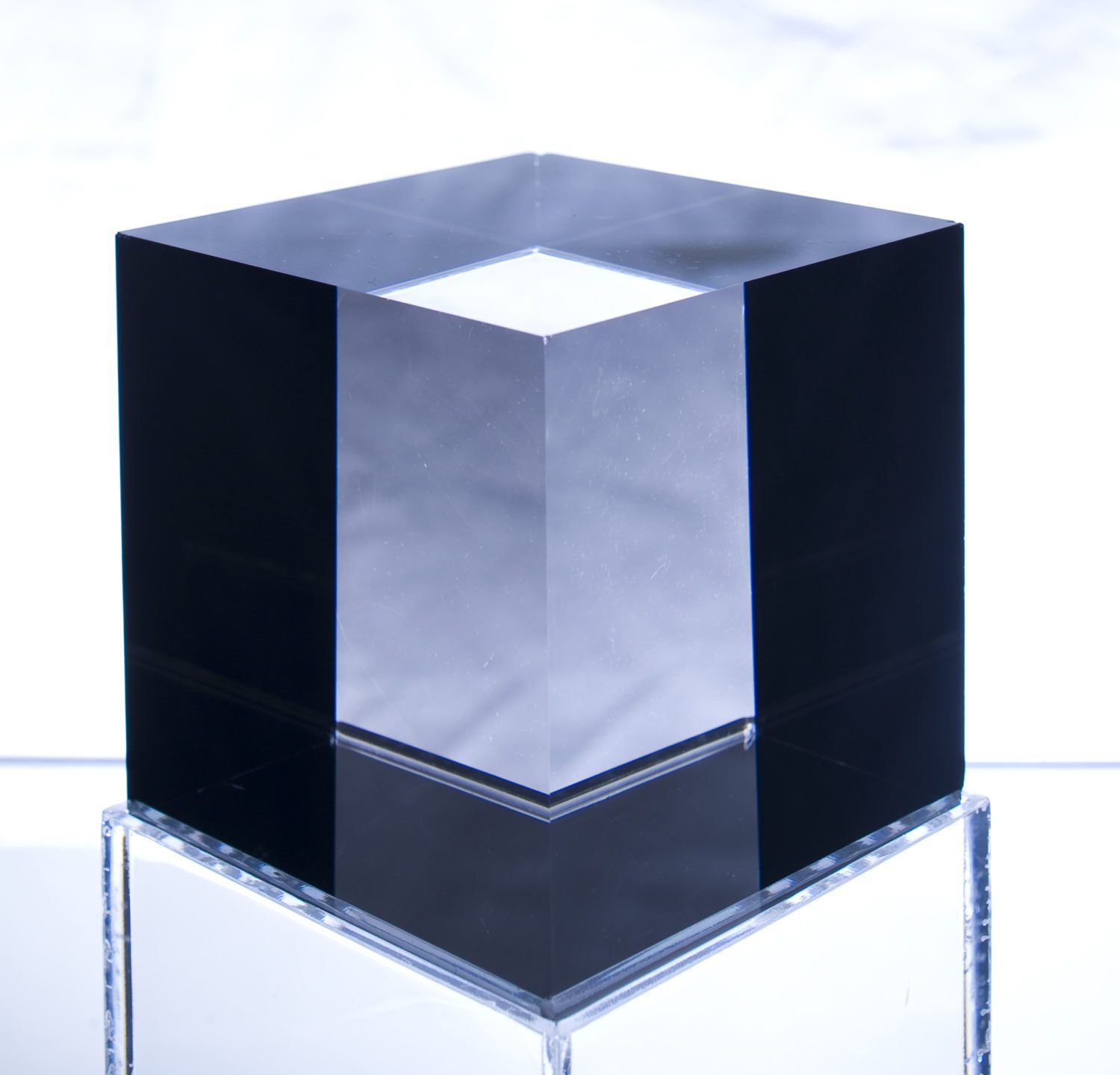

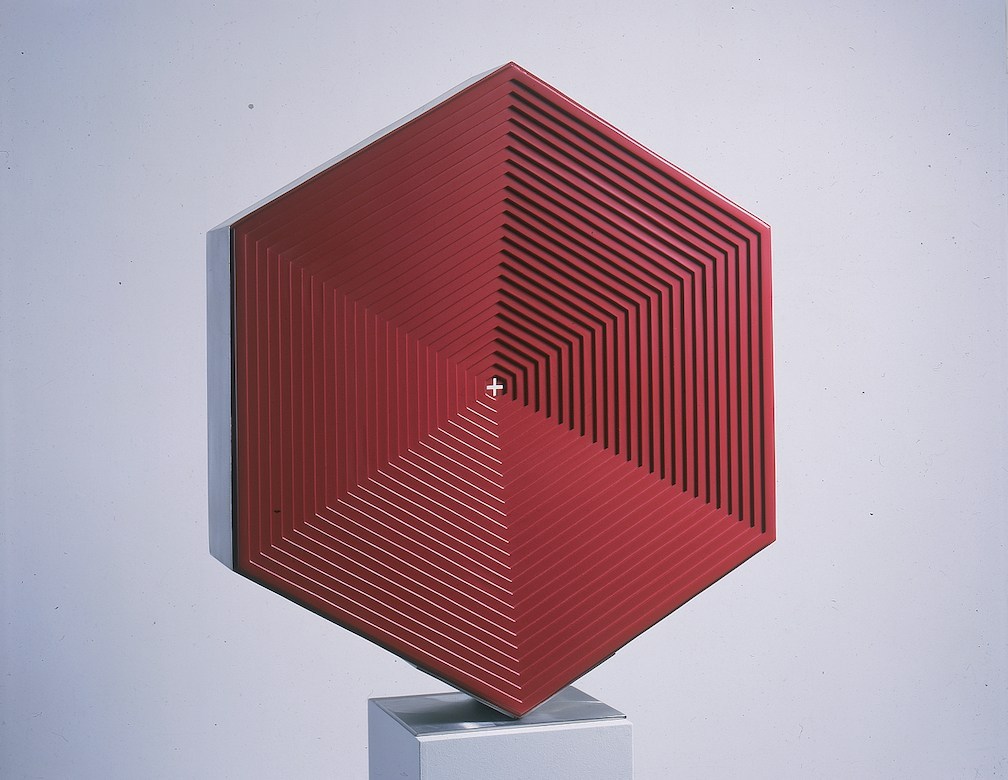

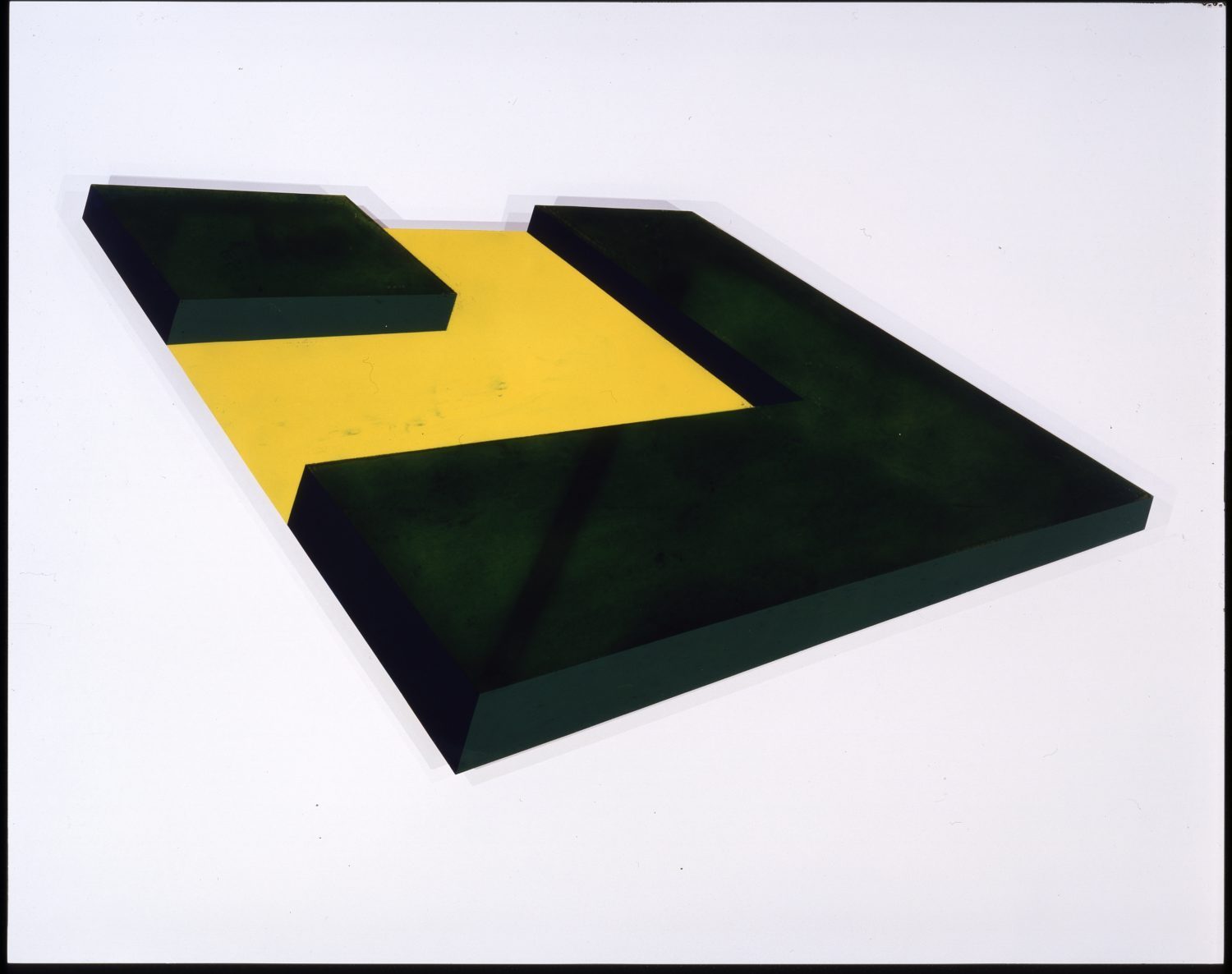

Light and Space works in the exhibition by now renowned artists demonstrated the use of industrial materials, including plastics, resins and polymers. Larry Bell’s “Bette and the Giant Jewfish” (1963) and “Untitled” (1969), large square boxes of vacuum-coated glass and chrome-plated metal, attracted refracted light. Tony DeLap’s “Fawkes” (1968), a shaped painting — he referred to it as a “hyperbolic paraboloid” — appeared to change shape as the viewer moved around it. And Ron Davis, who evolved from painting minimalist canvases to creating fiberglass and polyester resins, to building his 12-sided “dodecagon” wall sculptures, contributed his “Round” (1969) to the show; it is a dramatic abstract work of varied pigments.

Other Light and Space artists represented in the exhibition included Laddie John Dill, Robert Irwin, Craig Kaufman and James Turrell. The works of installation artists Jay McCafferty and Richard Newton were displayed there as well.

In the decade since “Best Kept Secret” was exhibited, UCI’s early efforts advancing innovative art have received increasing notice. Perhaps curator Grace Kook-Anderson plays a part in that recognition; as during the show’s display, she spent long hours promoting it and dialoguing with the exhibitors, often in public forums.

At UC Irvine today, mentoring continues as a prominent teaching style by faculty-artists including Kevin Appel, Juli Carson, Liz Glynn, Antoinette LaFarge, Daniel Joseph Martinez, Jennifer Pastor, Amanda Ross-Ho, among many others. This ongoing practice enables the art department to carry on its five decade legacy of empowering students to express their creativity unfettered by conventional standards.