The result is a pair of related series documenting both the decline of commercial and social bustle on his beloved Abbot Kinney Blvd., aka “The Hippest Street in the World,” and the simultaneous ongoing expansion and proliferation of street dwellings constructed by the unhoused population, part of a dynamic that has been neglected for years but has been exacerbated by the virus.

“As we were originally locked down and were seeing the photos of empty streets, venues [boarded up with plywood] and all of that, I was searching for a different point of view, beyond the obvious,” Shaffer tells the Weekly. In early May, he got into the habit of riding his bike around the neighborhood at sunrise, “for sanity and exercise,” and this really opened his eyes to the structures of the encampments mostly made from discarded, recycled, repurposed materials, and often with complex architectural creativity.

Alan Shaffer, The Hippest Street in America #8, 2020 (Asher Grey Gallery)

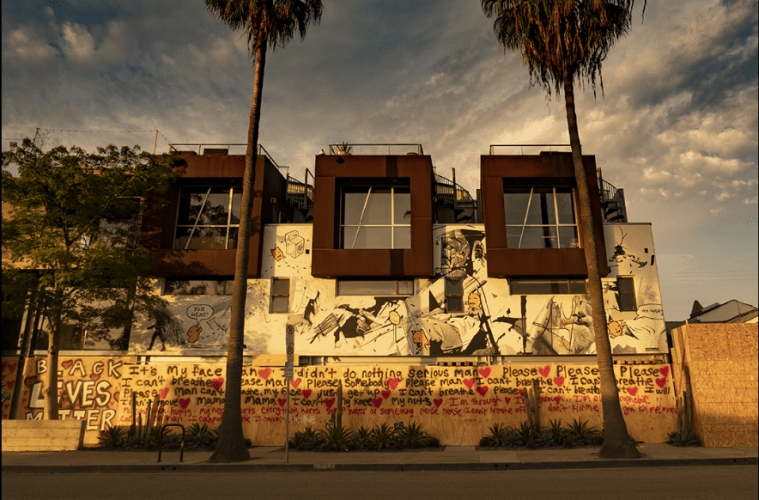

When the George Floyd uprisings took hold, Shaffer remembered vividly what had happened on Abbot Kinney during the Rodney King turmoil. By the end of May the street began to get boarded up in anticipation of potential troubles per what had just then transpired in Santa Monica. Shaffer’s morning bike rides were getting less serene by the day. The exhibition’s images were shot across two days between June 1-4, on bicycle, between Rose Ave. and Venice Blvd. and, as they say, “always west of Lincoln,” and “channeling Hotel California (specifically David Alexander’s cover shot) for the light.”

Alan Shaffer, The Hippest Street in America #4, 2020 (Asher Grey Gallery)

While Shaffer’s photography career is best known for his clean, heroic installation photography and intimate, character-rich portraiture of the local creative community, the unprecedented pressures and societal reorganizations of the summer spurred him to turn his tools and training toward projects that are both more personal and more journalistic. He’s a portraitist shooting scenes devoid of people; he’s a studio and gallery photographer who’s now shooting spontaneous, anonymous, outdoor street art tableaux and the substantial yet ephemeral shelters conjured by strangers. He’s a consummate professional who for those morning rides is also just another person with a camera and an urge to see and try to understand what is happening to us.

Alan Shaffer, Homeless Architecture #2, 2020 (Asher Grey Gallery)

Gorgeous golden light cascades across the scratchy warmth of plywood planks, spray-painted signs, posters of Floyd and other victims of police violence, BLM protestations and messages of love, and as dramatic skies and towering palms frame curious yurt-like structures in dramatic black and white. Questions arise about the balance of beauty and tragedy, documentation and action, hope and despair. When Shaffer first took these pictures, none of us had any idea that this many months later, those questions and more besides would remain so stubbornly, infuriatingly unanswered.

See It’s A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood at Asher Grey Gallery’s online exhibition through Artsy until January 31; ashergreygallery.com.

Alan Shaffer, Homeless Architecture #9, 2020 (Asher Grey Gallery)

Alan Shaffer, The Hippest Street in America #7, 2020 (Asher Grey Gallery)