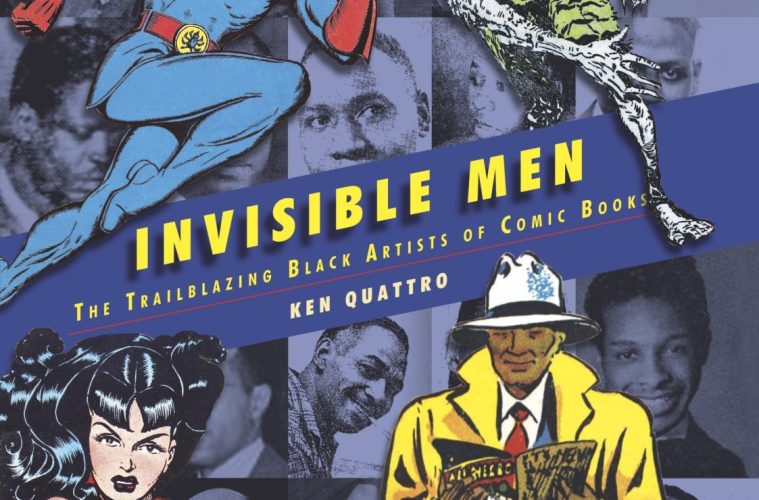

Quattro is correct of course, this convention afflicts social discourse at every level – but when it comes to the life and work of the 18 Black men whose biographies, challenges and accomplishments in the postwar American comics industry, making those distinctions and contexts clear is even more salient. In almost every case, these artists worked all but unsung, separate from their white colleagues and editors. Hired almost begrudgingly because of economic pressures and the need for cheap but talented labor, they created at the boundaries of representation – not only in terms of who was depicted in what race-based idioms within the comics themselves, but also in terms of who was tasked with creating them.

Voodah, 1945, Matt Baker (Courtesy of IDW Publishing)

In almost every case, these artists by day executed the visions of perfect white heroics, sexy Caucasian women as objects of desire, and villains and dupes whose caricatures landed on a spectrum from cringe-worthy to outright racist. On their own time, they created inclusive characters and storylines casting Black folks as heroes reaching back to elevate the mythologies of glory from the African continent, and looking to their present day surroundings to highlight the stories of contemporary public figures and neighborhood people of color. They were also frequently accomplished fine artists and graphic designers who created some of the most impactful and memorable visual depictions of activism from the Jim Crow-era civil rights movement.

March on Washington, 1963 by Alvin Carl Hollingsworth

The idea for Invisible Men started nearly two decades ago, when Quattro – a towering figure in comics lore and history, whose Comics Detective moniker and website is foundational to the genre – was writing an article about Matt Baker, the Black artist who in 1945 created Voodah, a character that is considered the first Black hero in a comic book aimed at white audiences.

Ace Harlem, by John H. Terrell (Courtesy of IDW Publishing)

In his Herculean research, Quattro read through what he describes as thousands of past issues of publications written by and for African Americans. “There was nothing in the white media, in newspapers or magazines at all, about Black comic book artists,” he has said. And that’s where the “detective” part came into play.

Black artists created heroes like Speed Jaxon, a character whom artist Jay Paul Jackson imagined visiting the hidden city of Lostoni, a kind of proto-Wakanda. Jackson also created Home Folks, an exuberant chronicle of daily life in the Black community set in places like the neighborhood record store. But then, there was Blond Garth, a sort of Tarzan joint where a white kid who is shipwrecked on a remote island is treated as a god by the locals.

Tales from the Land of Simba, November 1947, Elton Clay Fax (Courtesy of IDW Publishing)

Elton Clay Fax drew up NAACP posters, and at work, attended to U.S. military-inspired anti-Asian propaganda comics. Later, he worked on a George Dewey Lipscomb-penned series called Tales from the Land of Simba about “a boy whose courage and skill earned him the title Lion Master.” The book is filled with such stories of artists whose careers were bifurcated in this way, and aside from the excitement of discovering their stories at all, it is perhaps these juxtapositions that make the fraught parameters of their careers so clear.

E.C. Stoner, a descendant of one of George Washington’s slaves, was a fine artist of the Harlem Renaissance. His work included an illustrated biography of Rev. Ben Richardson – a beloved activist in the Black community who Stoner depicts literally getting beaten in the head by cops – alongside The Blue Beetle, the story of a white rookie cop who beats back alien invaders.

All-Negro Comics, No. 1, June 1947 (Courtesy of IDW Publishing)

All-Negro Comics was a collective of about half a dozen of these men, which launched in 1947 and was a literal game-changer, though even with demonstrably robust sales, they still had trouble getting shelf space in some places. Not monolithic, this imprint published a combination of both wholesome and egregiously unjust scenes from modern American Black life, as well as something both more nostalgic and futuristic regarding the diasporic community – creating an alternate universe in more ways than one, as only the great comic books can.